Monopolistic Competition; Meaning, Features and Market equilibrium

Monopolistic Competition; Meaning,

Features and Market equilibrium

![]() Khemraj Subedi, Associate Professor

Khemraj Subedi, Associate Professor

M.Phil (Economics)

Meaning

Monopolistic

competition is a market structure that lies in

between perfect competition and monopoly having features with large numbers of

buyers and sellers; imperfect information; low entry, and exit barriers; similar but differentiated products. Therefore, monopolistic

competition consists with features of both perfect competition and

monopoly. A monopolistic competition is

more common than pure competition or pure monopoly.

The first theoretical analysis of monopolistic competition

was simultaneously developed by two economists working independently of one

another: The British economist Joan Robinson (who introduced the concept in her

1933 book Economics of Imperfect Competition) and the American

economist Edward Hastings Chamberlin (whose ideas on the subject were published

in his Theory of Monopolistic Competition, published that same

year). While economists recognized that most businesses in the developed world

functioned under conditions of monopolistic competition or oligopoly, the

concepts were, because of their complexity, difficult to integrate into the

framework of existing economic ideas, whereas theories based on perfect

competition remained useful despite their limitations. It was not until the

1970s that mainstream economists commonly began addressing markets

characterized by monopolistic competition.

Definition

According to Prof. Leftwich – “Monopolistic Competition (or imperfect competition) is that condition of industrial market in which a particular commodity of one seller creates an idea of difference from that of the other sellers in the minds of the consumers.”

Features of Monopolistic Competition

1.

Large number of sellers: In a market

with monopolistic competition, there are a large number of sellers who

have a small share of the market.

2.

Product: differentiation: In monopolistic

competition, all brands try to create product differentiation to add an element

of monopoly over the competing products. This ensures that the product offered

by the brand does not have a perfect substitute. Therefore, the manufacturer

can raise the price of the product without having to worry about losing all its

customers to other brands. However, in such a market, while all brands are not

perfect substitutes, they are close substitutes for each other. Hence, the

seller might lose at least some customers to his competitors.

3.

Freedom of entry or exit: Like in

perfect competition, firms can enter and exit the market freely.

4.

Non-price competition: In monopolistic competition, sellers

compete on factors other than price. These factors include aggressive

advertising, product development, better demand, after sale

services, etc. Sellers don’t cut the price of their products but incur

high costs for the promotion of their goods. If the firms indulge in

price-wars, which is the possibility under perfect competition, some firms

might get thrown out of the market.

5.

Trade mark and patent right; Monopolist

use trademarks to ensure product differentiation. Likewise, they take exclusive

right of using new technology invented by them in the name of patent.

6.

Downward sloping Demand curve: Monopolist

tend to reduce price taking into consideration the elasticity of demand to

increase profit.

Conditions for the Equilibrium of an

individual firm under Monopolistic Competition

The

conditions for price-output determination and equilibrium of an individual firm

are as follows:

1. MC = MR

2. The MC curve cuts the MR curve from below.

In

the following Fig. 1, we can see that the MC curve cuts the MR curve at point

E. At this point,

·

Equilibrium price = OP and

·

Equilibrium output = OQ

Now,

since the per unit cost is BQ, we have

·

Per unit super-normal profit (price-cost) = AB or PC.

·

Total super-normal profit = APCB

Price-output determination under

Monopolistic Competition: Equilibrium of a firm

In monopolistic competition, since the product is

differentiated between firms, each firm does not have a perfectly elastic

demand for its products. In such a market, all firms determine the price of

their own products. Therefore, it faces a downward sloping demand curve.

Overall, we can say that the elasticity of demand increases as the differentiation

between products decreases.

Fig. 1 above depicts a firm facing a downward sloping, but flat demand curve. It also has a U-shaped short-run cost curve.

The

following figure depicts a firm earning losses in the short-run.

From Fig. 2, we can see that the per unit cost is higher than the price of the firm. Therefore,

·

AQ > OP (or BQ)

·

Loss per unit = AQ –

BQ = AB

·

Total losses = ACPB

Long-run equilibrium

If firms in a monopolistic competition earn

super-normal profits in the short-run, then new firms will have an incentive to

enter the industry. As these firms enter, the profits per firm decrease as the

total demand gets shared between a larger number of firms. This continues until

all firms earn only normal profits. Therefore, in the long-run, firms, in such

a market, earn only normal profits.

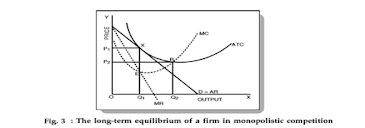

As we can see in Fig. 3 above, the average revenue (AR) curve touches the average cost (ATC) curve at point X. This corresponds to quantity Q1 and price P1. Now, at equilibrium (MC = MR), all super-normal profits are zero since the average revenue = average costs. Therefore, all firms earn zero super-normal profits or earn only normal profits.

It is important to note that in the long-run, a

firm is in an equilibrium position having excess capacity. In simple words, it

produces a lower quantity than its full capacity. From Fig. 3 above, we can see

that the firm can increase its output from Q1 to Q2 and

reduce average costs. However, it does not do so because it reduces the average

revenue more than the average costs. Hence, we can conclude that in

monopolistic competition, firms do not operate optimally. There always exists

an excess capacity of production with each firm. In case of losses in the

short-run, the firms making a loss will exit from the market. This continues

until the remaining firms make normal profits only.

Efficiency of firms in monopolistic

competition

· Allocative inefficient. The above

diagrams show a price set above marginal cost

- Productive inefficiency. The

above diagram shows a firm not producing on the lowest point of AC curve

- Dynamic efficiency. This is

possible as firms have profit to invest in research and development.

- X-efficiency. This is possible

as the firm does face competitive pressures to cut cost and provide better

products.

Limitations of the model of monopolistic competition

- Some

firms will be better at brand differentiation and therefore, in the real

world, they will be able to make supernormal profit.

- New

firms will not be seen as a close substitute.

- There

is considerable overlap with oligopoly – except the model of monopolistic

competition assumes no barriers to entry. In the real world, there are

likely to be at least some barriers to entry

- If

a firm has strong brand loyalty and product differentiation – this itself

becomes a barrier to entry. A new firm can’t easily capture the brand

loyalty.

- Many

industries, we may describe as monopolistically competitive are very

profitable, so the assumption of normal profits is too simplistic.

Perfect Competition VS Monopolistic Competition VS Monopoly

A

monopolistically competitive firm faces a demand for its goods that is

between monopoly and perfect competition. Figure 8.4a offers a reminder

that the demand curve as faced by a perfectly competitive firm

is perfectly elastic or flat, because the perfectly

competitive firm can sell any quantity it wishes at the prevailing market

price. In contrast, the demand curve, as faced by a monopolist, is the

market demand curve, since a monopolist is the only firm in the market, and

hence is downward sloping.

Above figure shows perceived

Demand for Firms in Different Competitive Settings. The demand curve faced by a

perfectly competitive firm is perfectly elastic, meaning it can sell all the

output it wishes at the prevailing market price. The demand curve faced by a

monopoly is the market demand. It can sell more output only by decreasing the

price it charges. The demand curve faced by a monopolistically competitive firm

falls in between.

The following table

clarifies the difference amongst Perfect competition, Monopolistic competition

and Monopoly.

|

Market

Power |

Number

of Firms |

Efficient

Market |

Product

Differentiation |

Profits |

Elasticity of Demand |

|

|

Perfect

Competition |

None |

Infinite |

Yes |

No |

Normal profits |

Perfect

Elasticity |

|

Monopolistic

Competition |

Low |

Many |

Not

efficient |

Mild

levels |

Super normal in short-term / normal in long-term |

Highly

elastic in long-run |

|

Monopoly |

High |

One |

Not

efficient |

Only

across industries |

super normal |

Inelastic |

Number of Firms

First of all, the number of firms is relatively low.

As there is more than one firm, it does not classify as a monopoly, but

significantly fewer than under perfect competition. This is due to the fact

that in monopolistic competition, many firms slightly differentiate themselves

from each other.

As a result, new entrants seek to add value in a

slightly different way. In the end, this limits the number of firms that are

willing and able to enter the market; but not significantly enough to deter the

plethora of competitors.

Market Power

It is also important to highlight that in monopolistic

competition, firms actually have very low market power. Whilst it sounds

similar to monopoly; the ability of individual firms to set prices in the

market is non-existent. None really have significant market share, so are

unable to force the hand of competitors. So unlike a monopoly, firms in

monopolistic competition cannot set prices; yet they have more power than under

perfect competition.

Efficiency

Firms in both a

monopoly and under monopolistic competition are inefficient; largely in

contrast to perfect competition. To explain, firms in monopolistic competition

are inefficient due to two main reasons: first of all, it operates with excess

capacity; and second of all, it charges a price that is in excess of marginal cost.

Product Differentiation

Under monopolistic competition, firms slightly

differentiate their products. For example, tea bags rely on quality and brand

name to differentiate, yet under a perfectly competitive market, they would be

exactly the same.

Profits

In a monopolistic market, profits can range from

supernormal in the short-term, to ordinary in the long-term. By contrast, perfect

competition is generally locked in equilibrium, only earning small amounts of

profit. We then have a monopoly market, which, quite understandably, makes

supernormal profits.

Elasticity of Demand

Demand in

monopolistic competition can be highly elastic as there are a number of

competitors. Switching costs are low, so consumers are easily able to switch

to substitute goods.

By contrast, perfect competition is perfectly elastic due to the infinite

number of competitors. We then have monopolies which are purely inelastic. This

is largely as a result of the lack of competition which leaves consumers with

little choice but to pay the higher prices.

Summary and Conclusions

Monopolistic competition refers to a market

where many firms sell differentiated products. Differentiated products can

arise from characteristics of the good or service, location from which the

product is sold, intangible aspects of the product, and perceptions of the

product.

If the firms in a monopolistically competitive

industry are earning economic profits, the industry will attract entry until

profits are driven down to zero in the long run. If the firms in a

monopolistically competitive industry are suffering economic losses, then the

industry will see an exit of firms until economic profits are driven up to zero

in the long run.

A monopolistically competitive firm is not

efficient because it does not produce at the minimum of its average cost curve

or produce where P = MC. Thus, a monopolistically competitive firm will tend to

produce a lower quantity at a higher cost and charge a higher price than a

perfectly competitive firm.

Monopolistically competitive industries do offer

benefits to consumers in the form of greater variety and incentives for

improved products and services. There is some controversy over whether a

market-oriented economy generates too much variety.

References

1. Baumol, William,

1982. ―An Uprising in the Theory of Industrial Structure‖, American Economic

Review, 72(1), 1-15.

2. __________, J. C. Panzar and Robert Willig,

1982. Contestable Markets and the Theory of Industrial Structure. San Diego:

Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

3. Becker, Gary,

1965. ―A Theory of the Allocation of Time‖, Economic Journal, 75(299), 493-517.

4. Bishop, Robert,

1964. ―The Theory of Monopolistic Competition after Thirty Years: The Impact on

General Theory‖, American Economic Review, 54(3), 33-43.

5. Boulding, Kenneth,

1966. Economic Analysis, Volume I: Microeconomics. New York: Harper & Row.

6. Chamberlin,

Edward, 1933. Theory of Monopolistic Competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

7. __________, 1936.

―Monopolistic Competition and the Productivity Theory of Distribution‖,

Explorations in Economics. New York: McGraw-Hill, 237-249. Reprinted in William

Fellner and Bernard F. Haley, editors, 1951. Readings in the Theory of Income

Distribution. Philadelphia: Blakiston, 143-157.

8. __________, 1948. ―An Experimental

Imperfect Market‖, Journal of Political Economy, 56(2), 95-108.

9. __________, 1950.

―Product Heterogeneity and Public Policy‖, American Economic Review, Papers and

Proceedings, 40(2), 85-92.

10. __________,

1951. ―The Impact of Recent Monopoly Theory on the Schumpeterian System‖,

Review of Economics and Statistics, 33(2), 133-138.

11. __________,

1957. Towards of More General Theory of Value. New York: Oxford University

Press.

12. Call, Steven and

William Holahan, 1980. Microeconomics. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

13. Clark, John

Maurice, 1940. ―Toward a Concept of Workable Competition‖, American Economic

Review, 30(2), 241-256.

14. __________,

1957. Economic Institutions and Human Welfare. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 15.

Dewey, Donald, 1975. Microeconomics: The Analysis of Prices and Markets. New

York: Oxford University Press.

16. Ekelund, Robert

and Robert Hébert, 1997. A History of Economic Theory and Method. New York:

McGraw-Hill.

17. Foss, Nicolai,

1997. An Interview with Brian J. Loasby. Working Paper 97-9, Department of

Industrial Economics and Strategy. Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School.

18. Friedman, Milton, 1953. Essays in Positive

Economics. Chicago: University of Chicago.

19. __________,

1976. Price Theory. Chicago: Aldine Publishing.

20. Greenhut,

Melvin, George Norman and Chao-Shun Hung, 1987. The Economics of Imperfect

Competition: A Spatial Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

21. Harrod, Roy,

1952. Economic Essays. New York: Harcourt Brace.

22. Holcombe, Randall, 1989. Economic Models

and Methodology. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

23. Holt, Charles,

2003. ―Economic Science: An Experimental Approach to Teaching and Research‖,

Southern Economic Journal, 69(4), 755-771.

24. Hunter, Alex,

1955. ―Product Differentiation and Welfare Economics‖, Quarterly Journal of

Economics, 69(4), 533-552.

25. Kaldor,

Nicholas, 1934. ―Mrs. Robinson‘s ‗Economics of Imperfect Competition‘ ―,

Economica. New Series 1(3), 335-341

Comments

Post a Comment